Climate Justice Means Correcting The Colonial Wrongs Done To Over-exploited States

By: Morgan Hollie, Staff Researcher at Diaspora Rising

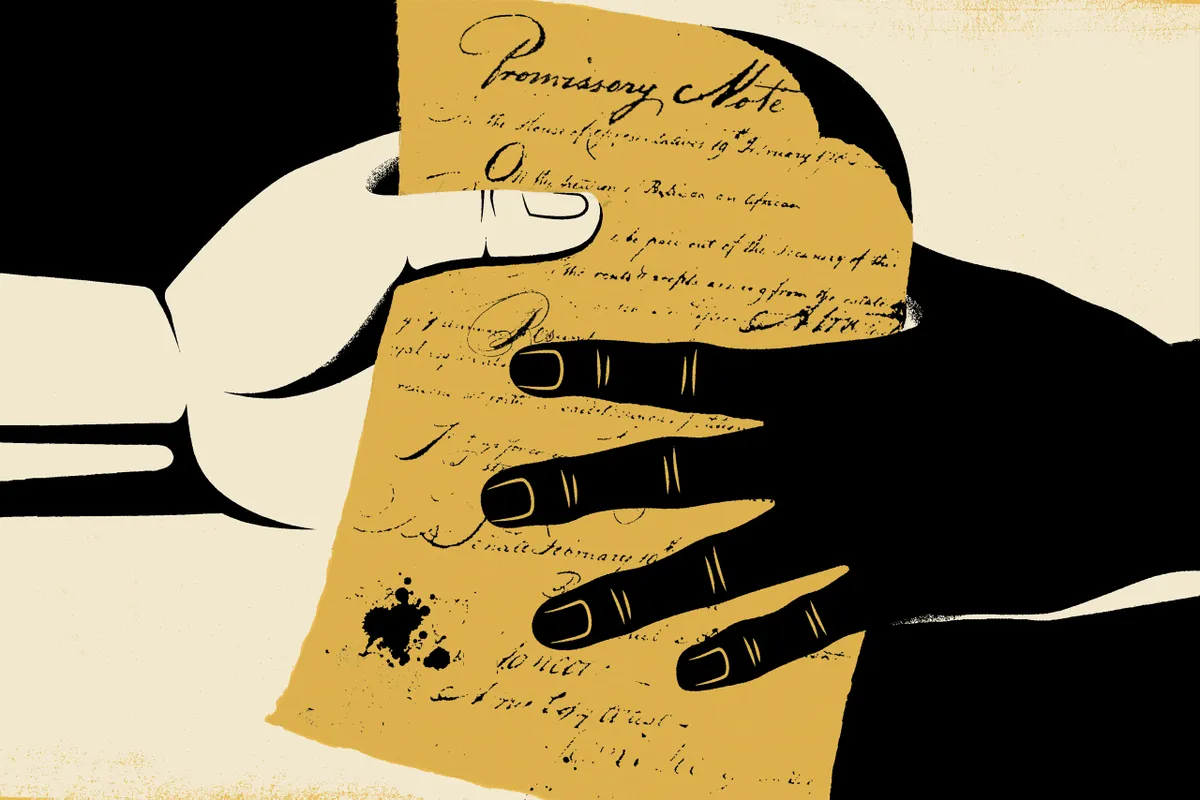

Despite the fervent pledges of Western world leaders to combat climate change in the global south at the last COP26 summit, the United States and United Kingdom have already begun backtracking on the promises made last October. The US and UK both made a number of fervent pledges during the Glasgow summit last October to help curtail deforestation, reduce carbon emissions, and fund climate change adaptation strategies for global south states. However, just months after the summit American and British legislators have hit significant roadblocks in delivering on their promises. Leaders from Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific Islands, whose countries face the most perilous effects of climate change, told COP26 delegates that it is time for wealthy industrialized states to produce the funds they promised. The promises have been made, now these states must keep their word.

Addressing world leaders and delegates at the COP26 Summit in Glasgow, Prime Minister Mottley castigated wealthy high-emitter states for their failure to keep a 2009 promise to deliver $100 billion per year in climate finance to countries in the global south. Wealthy high-emitter states previously committed to delivering the funds “through 2025,” however estimates indicate that the promise not be met until 2023. Wealthy states who industrialized through resource extraction and rampant burning of fossil fuels are chiefly responsible for the overwhelming bulk of greenhouse gas emissions, but have persistently resisted delivering on their 2009 promise, fearing of the ramifications of accepting liability for global environmental degradation.

The United States and United Kingdom, alongside several wealthy European states, pledged additional funding for adaptation and mitigation strategies in the global south . In the United States, President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” bill, which would have devoted $555 billion to fund clean energy development and climate change mitigation strategies, failed to pass the US Senate, effectively killing the bill. The United Kingdom, which also pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2030, has recently greenlit a new oil and gas field project in the North Sea. The new UK project is moving ahead despite COP26 President and UK COP26 lead Alok Sharma saying he is against the project, and that the UK should be “building forward on renewables.” Additionally, while twenty-two countries pledged to move away from carbon-burning internal combustion engines by 2035, major automaking countries, including the US, Germany, France, and Japan, did not sign the pledge.

African and Caribbean countries will suffer catastrophic effects of climate change, despite producing low levels of greenhouse gas emissions. Collectively, African states contribute around 5% of the globe’s greenhouse gas emissions. Emissions from Caribbean states account for less than 1% of global emissions. Despite low emissions, African and Caribbean states have been routinely described as existing on the “frontlines” of the climate crisis, due to the inordinate damage both regions are likely to experience due to climate change. Experts have sounded the alarm that lives and livelihoods in both regions will be threatened by increasingly destructive tropical storms, rising sea levels, and irregular rainfall patterns. Caribbean states are especially vulnerable to coastal hazards, such as hurricane surges and flooding, with more than a quarter (27%) of the region’s population living in coastal zones. Irregular rainfall patterns across Africa are likely to cause more frequent droughts and decimate agricultural production, which will have severe consequences for food security and economic stability in both regions. African and Caribbean states did not arrive at their present troubling situation on their own. Unequal distribution of financing for climate change adaptation and mitigation and loss and damage follows patterns of international exploitation and inequality which stem from the colonial past.

Wealthy states of the global north were able to industrialize through colonial systems of extractive exploitation, including through the imperial scramble to control resources across Africa, Asia, and in the Americas. To enrich sites of empire in Europe, British colonists plundered metals, minerals, and crops, and re-settled already developed human civilizations, impacting pre-colonial social and cultural landscapes and devastating natural ecosystems. Across Africa, colonists seeking to profit from the continent’s wealth of natural resources built mines and oil refineries, which continue to adversely impact health and wellbeing in many parts of the continent. The 1930s discovery of oil in Nigeria’s Niger Delta region prompted the British colonial administration to grant Shell-British Petroleum complete control over the oil producing region. Since then, frequent oil spills have decimated vital sources of drinking water, agricultural lands, and crucial grazing grounds for livestock and other animals. The burning of natural gas during oil and gas production and processing, known as flaring, releases harmful black carbon, methane, and volatile organic compounds – dangerous pollutants which have been linked to an increased prevalence of certain cancers and respiratory diseases in Nigerian communities surrounding flaring sites.

Like in Africa, environmental degradation in the Caribbean region has an important colonial legacy—one rooted in slavery and the establishment of plantation labor camps. Slavery and colonization of the Americas and Caribbean islands by the British, Dutch, French, Spanish, and Portuguese empires resulted in widescale engineering of physical environments to make way for the proliferation of sugarcane, coffee, tobacco, and other plantation crops. In Haiti, for example, the French colonial government cleared forests to profit from mahogany wood exportation and to clear the way for profitable sugar plantations worked by enslaved African people. In the present day, Haiti’s landscape is still marked by deforestation and the lack of trees means that even moderate rainfall can bring about deadly landslides and flooding. Haiti, and other small island developing states, are in urgent need of funding to overcome global income inequalities between countries and protect their populations and ecosystems.

While some wealthy nations have taken steps towards addressing climate change mitigation, the steps taken after , present funding commitments do not go far enough to address the resource imbalances between non wealthy states and wealthy states, many of which industrialized by exploiting land, resources, and people in the global south. If climate change is to be meaningfully mitigated and addressed, it is necessary to correct the economic wrongs of the past and present by funding resources for states on the frontlines of climate change to protect the lives, homes, and wellbeing of their populations. Wealthy states of the global north must be made to recognize their responsibility to redirect resources towards combatting the global climate crisis they had an outsized hand in creating. As Prime Minster Mottley has noted, a failure to do so will be measured in “lives and livelihoods” in the global south.